Training & Task Management

“When we learn something new about our operation and its processes – we improve. But, when we forget – product quality, profitability and customer satisfaction slips!”

OperationImprovement.com

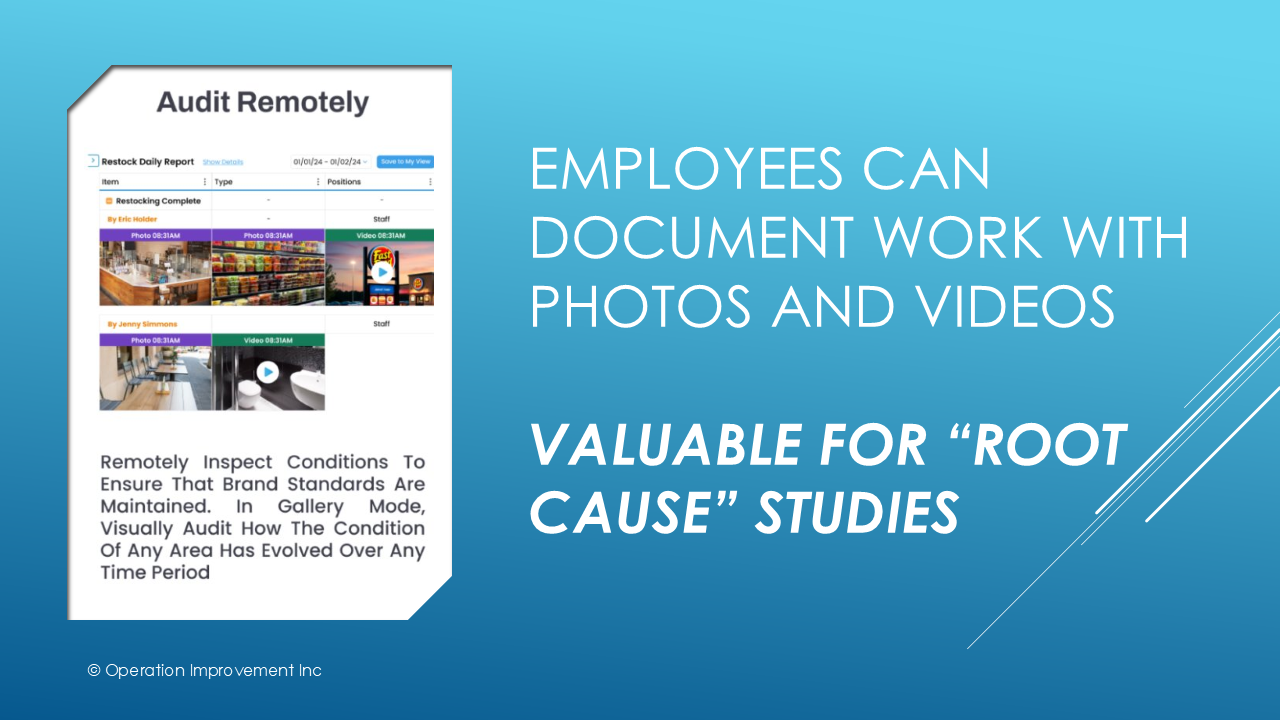

After new and better processes have been established and some initial training has taken place, there remains one big challenge to sustained improvement. Our desire is “a correct and consistent operation”.

But, under pressure, people are tempted to take shortcuts. Over time, employees do forget and sustained adherence to a plan is difficult to maintain. In short, after an improvement initiative, companies sometimes backslide.

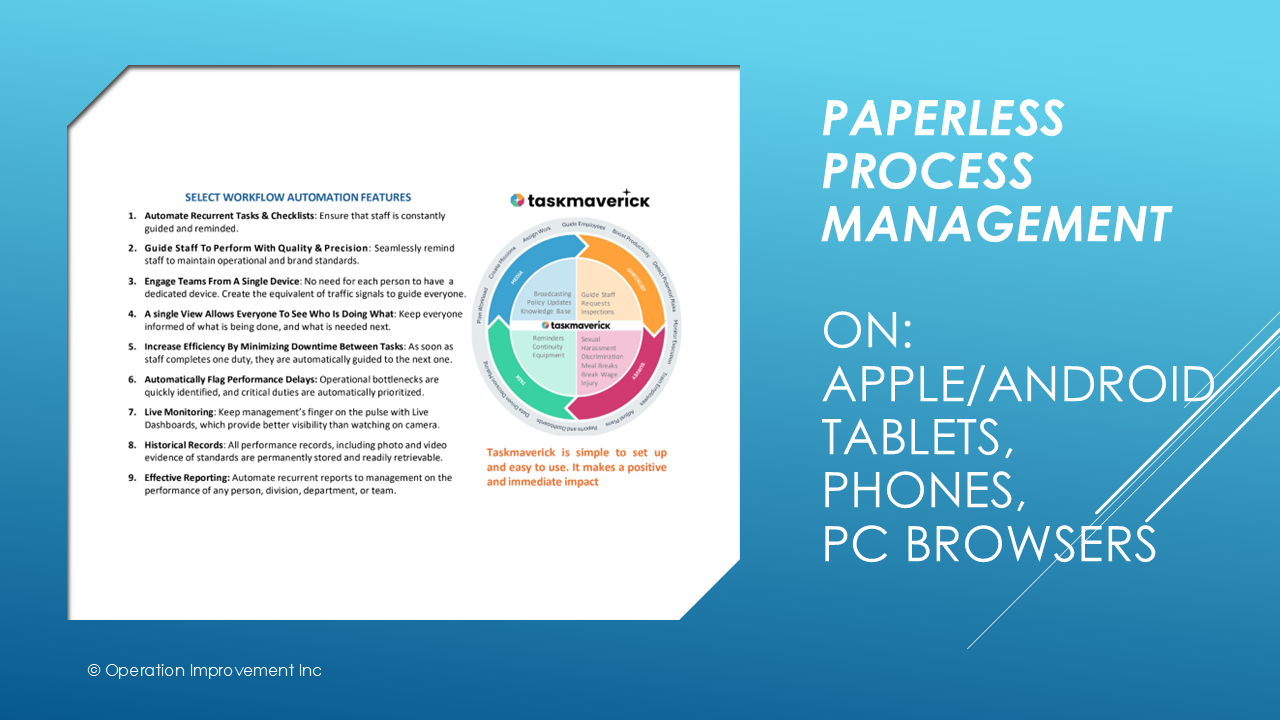

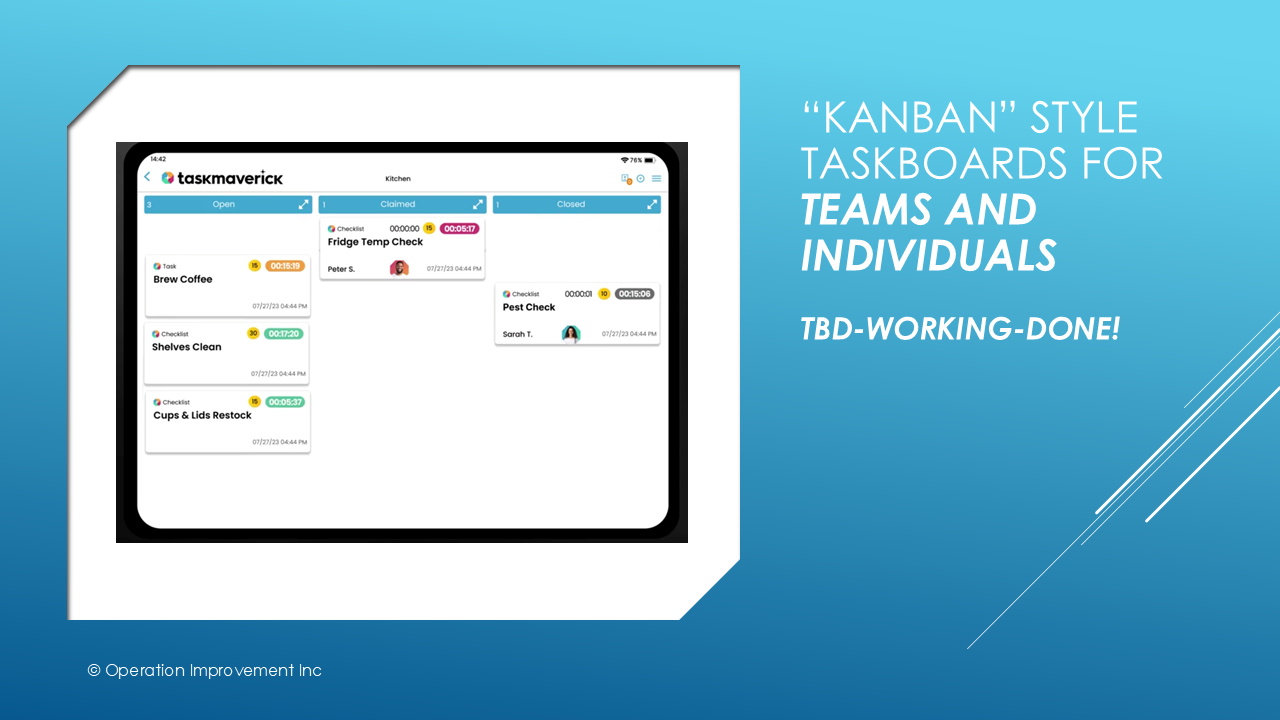

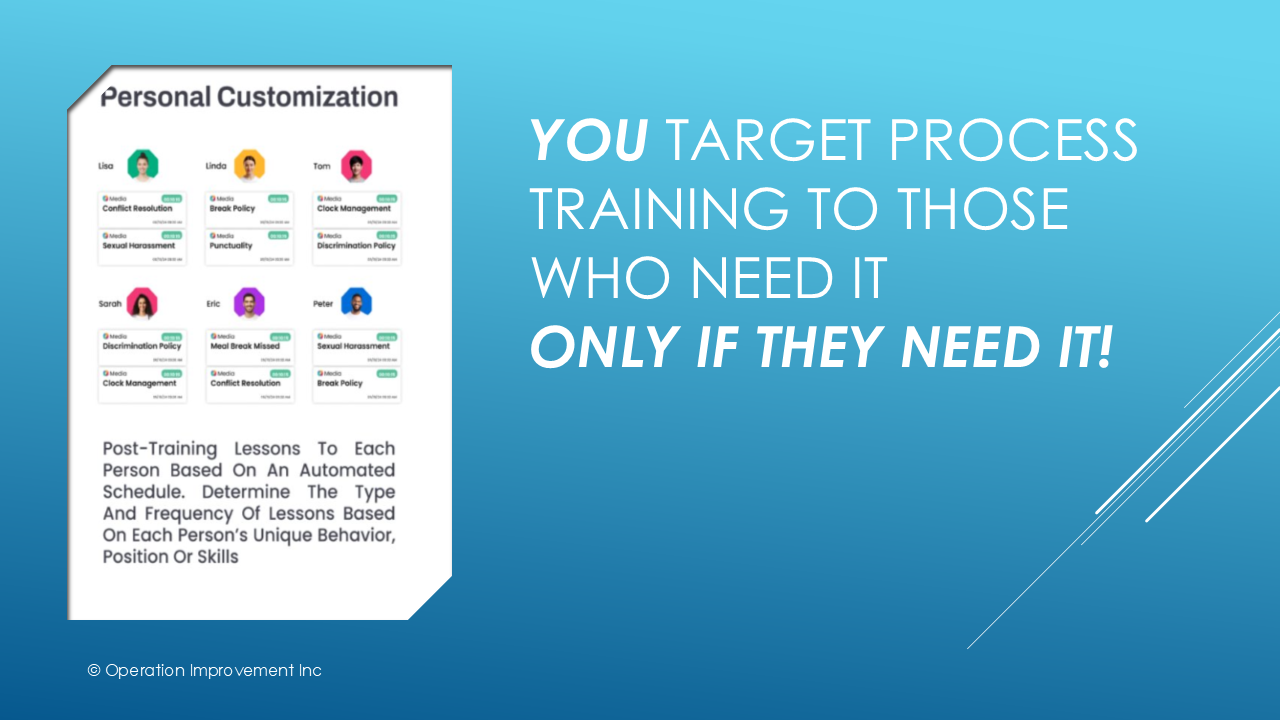

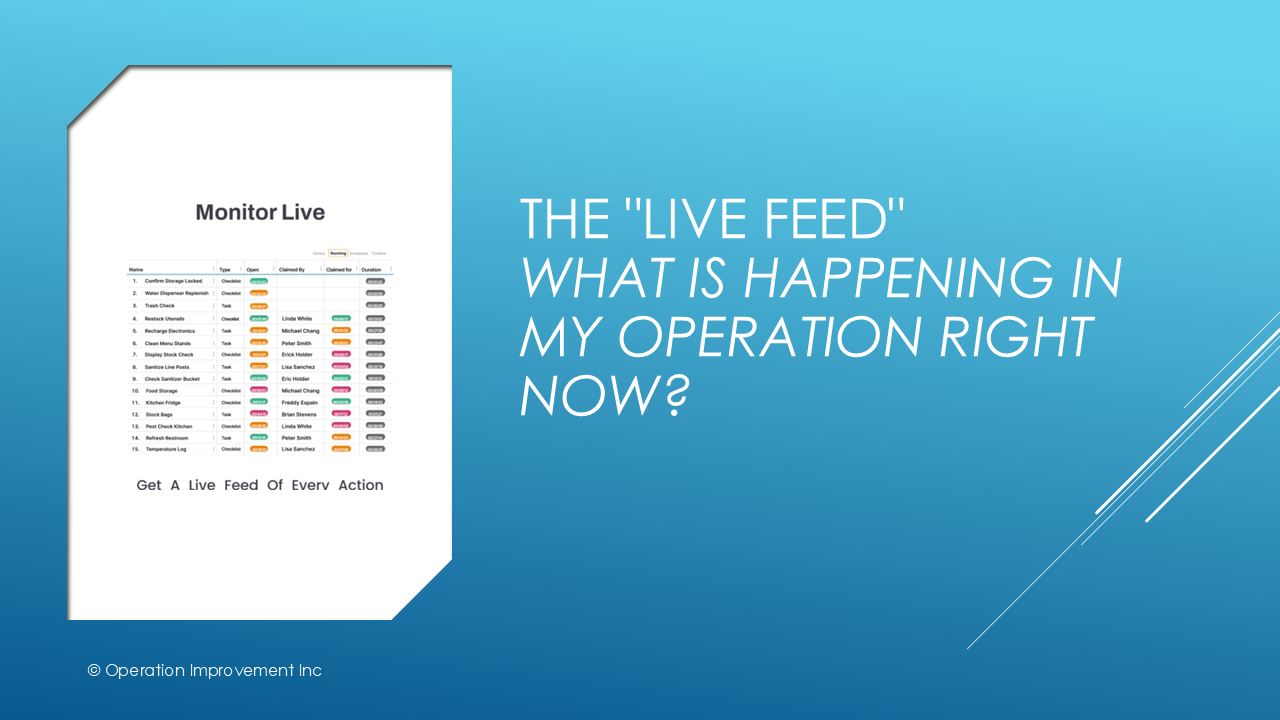

Taskmaverick is easy-to-use, affordable, “software as a service”. It requires no hardware other than the Apple and Android tablets and phones you probably already have. Once configured for your most critical processes, it supports sustained compliance over time through micro-training in one to three minute sessions, how-to videos, and task reminders so that nothing planned is forgotten.

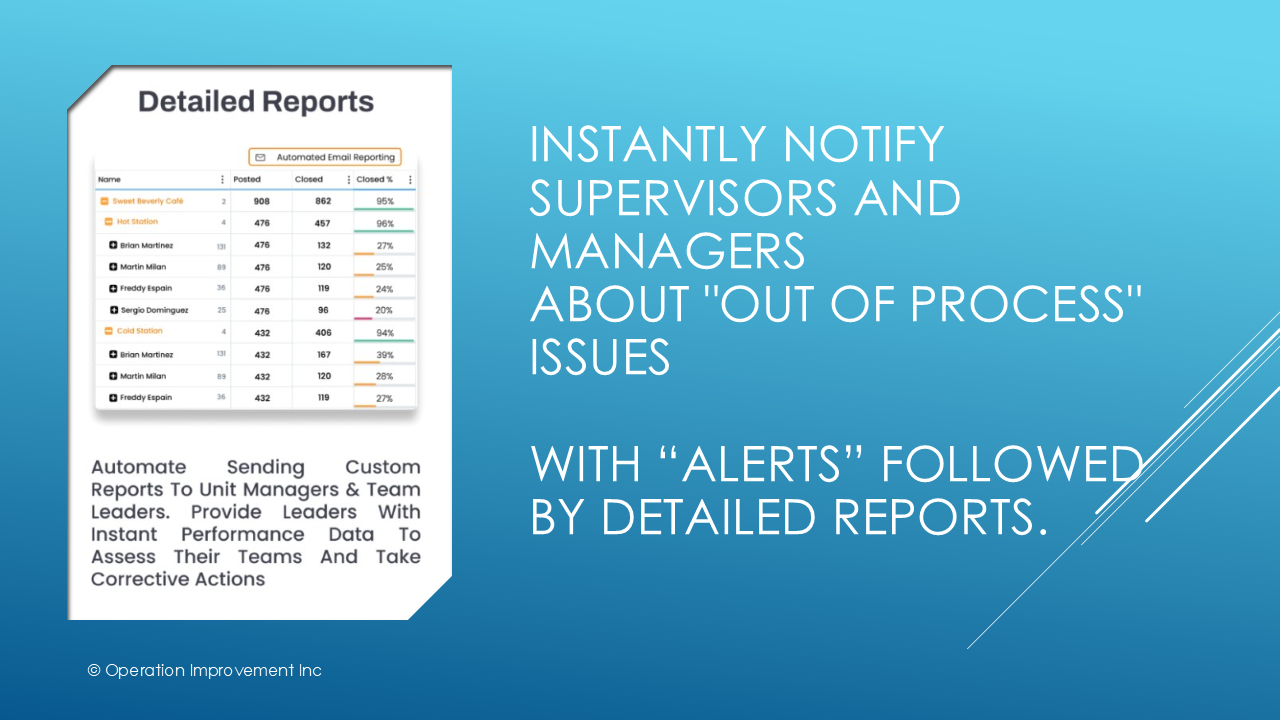

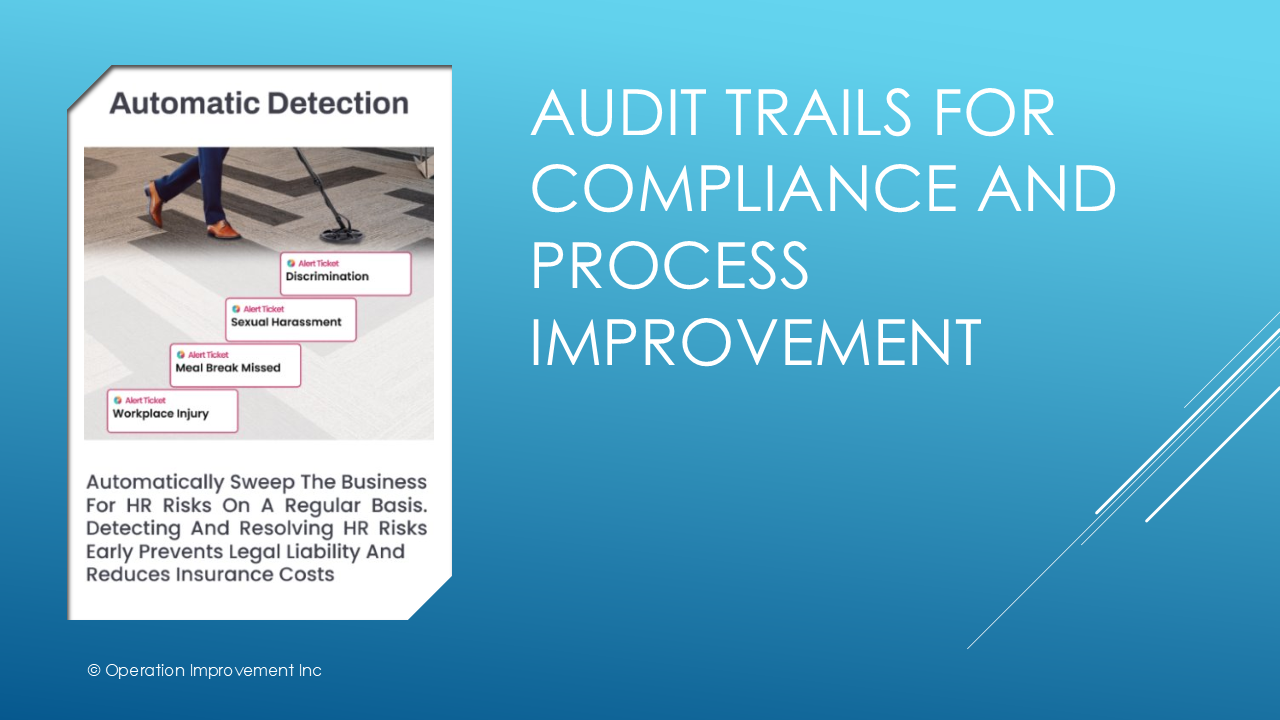

It adapts as priorities shift, and has mechanisms to handle and escalate “out of process” conditions – alerting supervisors and managers when it is not possible for things to go according to plan.

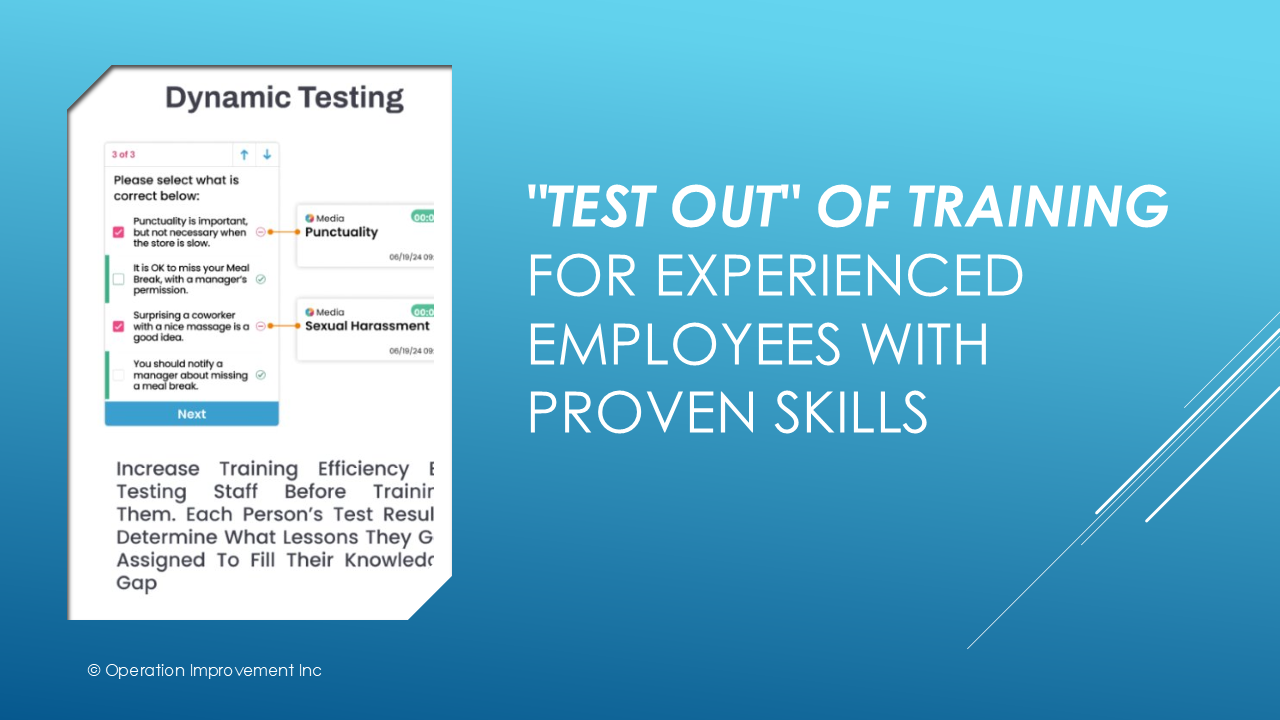

You can begin using Taskmaverick in one high-reward area, HR onboarding, skills certification training, or maintenance for example. Then scale into other areas as your organizational culture becomes familiar with it.

Take a look at this high-level overview of Taskmaverick and use the contact form or schedule an initial call on my calendar. I’ll tell you more and answer any questions. We will get you started on Taskmaverick ASAP!

(Be Sure to read “It’s Hard to Make Things Easy” – The Secret to Great Training)