Call Center Strategy

“Happier Customers”

Call centers, now also called contact centers, have wrestled with the dilemma of service quality versus cost for decades. Wrong assumptions about what is important in call center operations lead to a no-win alternative: either throw money at the problem or live with customer dissatisfaction. Take a moment to review the conventional way of approaching this dilemma and then check out a better approach.

A LITTLE TELEPHONE HISTORY

One hundred years ago, a hands-on Danish mathematician climbed into Copenhagen manholes to study telephone traffic. Without knowing who called, why they called, what was discussed, or any other particulars, he began to mathematically describe what he saw.

By mathematically modeling call arrival times, Agner Krarup Erlang found that average call volumes and durations could predict busy signals, line utilization, and the number of rings until a circuit was connected. This, of course, applied to “calls in the wild”—anyone calling anyone for any reason or for no reason at all.

One interesting characteristic of Erlang calls is that call duration is heavily skewed to a shorter duration. Most calls are short, some are longer, and a few calls straggle in with extraordinarily long call duration.

Citing Erlang, conventional call center wisdom makes two big mistakes.

THE CONVENTIONAL APPROACH

Call centers look for ways to create large pools of agents. This is an “Erlang” strategy for coping with variation driven by call arrival times.

This might make sense in cases where there are only a few agents, and Erlang (“Erlang-C”) calculations support this. It’s obvious that a small team of agents will be able to take more calls and achieve higher utilizations than if they worked independently.

However, Erlang-C also predicts 90%-95% utilizations and short call hold times when call center sizes reach fifty to one hundred agents. This prediction rarely if ever holds true. Do we really think call center problems go away when they super-size their operations?

The advantages of agent pools diminish rapidly when they increase above the size of a small team. Something else begins to influence productivity!

Since popular workforce management packages have only Erlang call durations built into their assumptions, and since most call distribution systems are built to encourage large agent pools, tactical managers are taught to fight variation rather than properly manage it.

In the well-intentioned (but wrong) schools of call center management, supervisors are often taught these things:

- Insist that agents answer the phone as quickly as possible.

- Insist that agents complete the call as quickly as possible.

These two things are almost always improperly measured. They are treated as performance metrics and not process metrics. This wrongly prioritizes average duration over correct call handling.

It’s hard to believe—but it actually happened. One call center manager, in an attempt to motivate faster call handling, put on a fireman’s hat and ran through the floor shouting “Get off the phone!” whenever wait times spiked.

While extreme, this story illustrates a broader truth: many managers respond to service level pressure by pushing agents to take shortcuts, regardless of process quality or consistency.

WHAT CALL CENTERS CAN MANAGE

Processing time is a signature metric of a correct and consistent process.

A medium-rare steak takes a predictable number of minutes to cook (plus or minus). A haircut, updating an email address in a computer system, a 100-mile drive between two cities – these all take a very predictable amount of time if done correctly and consistently. Call center processes should be no different.

Well-defined processes take as long as they take, until and unless they are reengineered. Unfortunately, the urgency of ringing phones blind many managers to the issue at the heart of call center effectiveness. Agents are, in effect, continually being asked to “drive faster”—and the consequence is increased process variability.

Erlang’s traffic engineering formulas only take into account variability in call arrival times but have no real management advice on every other potential source of variation. It is, in effect, a “no smoking” policy in a burning house.

THE TOTAL VARIABILITY PICTURE

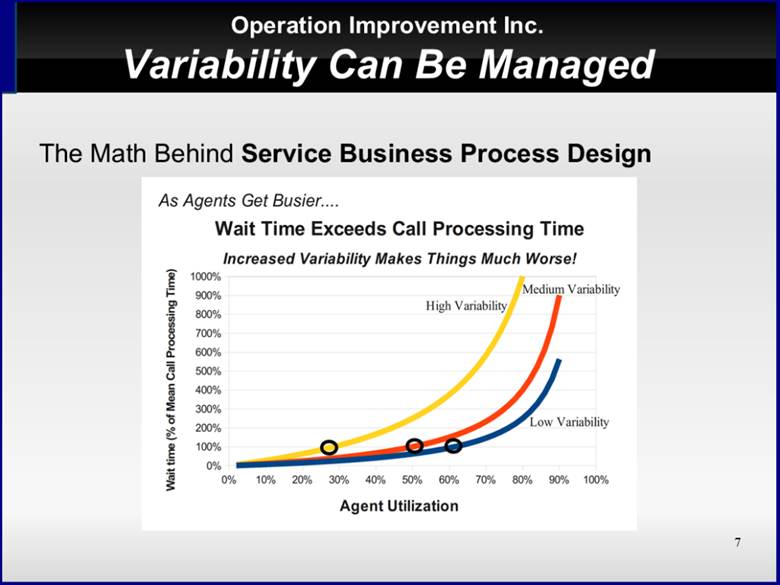

Take a look at the Pollaczek–Khintchine equation that describes the relationship between wait time, call processing time, utilization, and total call handling variability. The three lines represent estimated average wait times with increasing levels of variability.

Figure 1 Wait times increase rapidly as call handling variability rises

Erlang demonstrated this “hockey-stick” effect with just arrival times, but this pattern is true of every source of call handling variation in the call center operation.

Instead of just focusing on call handling time, measure and monitor the variability of call handling time. Then begin to study what factors can make handling times more consistent and reduce variability

Managing and lowering this source variability will rapidly improve call center utilization, reduce wait times, lower costs, and improve the quality of customer service. The prime directive of the operations manager is to manage variability by running correct, consistent, and capable processes.

If the only source of variability was in call arrival, managing this would simply be a matter of scheduling – of contouring start times and staffing levels to demand of service.

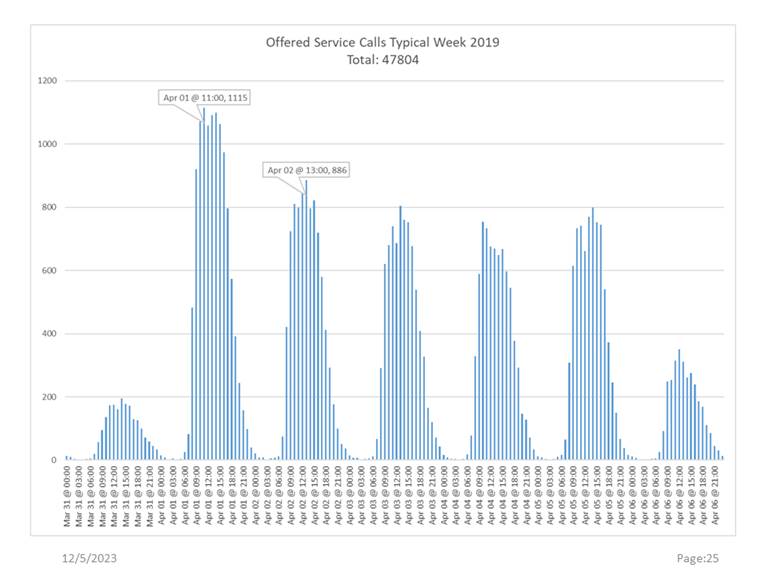

Look at this actual data from a high-volume call center. Week after week, this same arrival pattern reliably appeared in the 15-minute interval data.

Figure 2 Number of Calls Arriving in 15 minute intervals for an entire week

Exceptions to this repeating pattern did occasionally occur, but they were exceptions with an identified cause. In infrastructure support, a major outage can overwhelm the best operation. In sales and marketing customer support operations are sometimes blindsided by “surprise” ad campaigns announcing a new product or service.

MANAGING VARIABILITY APPROACH

Of course, the usual metrics of wait times, queue backlogs, and call volumes must be monitored; but avoid immediately aggregating them into daily or monthly statistics. Start with time series analysis and strive for near-real time data updates before rolling this up into a daily or monthly performance analysis. Monitor call variability in a similar manner.

Analyze and group calls of like kind – both in duration and content. Create small right-sized “Erlang” teams to handle calls of the same type. Use advanced call routing techniques (e.g. “skill based routing”) with caution to be sure you can control what calls go to what agents.

Walk through in writing what should happen with each call type. Create career paths for agents so that new agents can quickly become productive on simpler call types, and gradually transition to more complex ones as they gain experience.

Track the same metrics discussed so far and in the same manner for each team/call type. Be prepared to “flex” staffing by moving senior agents back to familiar and simpler call types

Finally, staff each team’s capacity to meet the demand profile of their call type, and not the aggregate call arrival profile of the entire organization.

In short, improving call center performance isn’t just about scheduling and scaling—it’s about systematically managing variability. When call handling processes are consistent, predictable, and aligned with agent capability, the entire operation becomes more effective, responsive, and affordable.

To learn more about this approach, visit https://effectivecallcenters.com, and read about some of our client successes.

Copyright © 2025 Operation Improvement Inc. All rights reserved.